A third article I originally wrote for the BeerHeadZ website, first published in October 2018. We’ve all had it. That disappointing moment after you’ve handed over your hard-earned wonga and the barkeep plonks a pint in front of you and you know, by sight or smell alone that it just ain’t right. That’s OK, these things happen from time to …

From the Archives: How much do you value your pint?

Here’s a second article I first wrote for the BeerHeadZ website as a follow-up to my ‘Journey with beer‘ post, which originally appeared in October 2019. Beer has historically been perceived as ‘the drink of the working man’ and, as such, has been expected to be cheap and accessible to all. But is this still the case now? ‘Cheap’ beer …

From the Archives: My journey with beer.

This is an article I wrote for the BeerHeadZ website, originally published in October 2019. My earliest recollection of tasting beer was in the kid’s outside area of a pub, somewhere on the outskirts of Portsmouth, when I asked my dad if I could taste his beer. I took a swig and my face screwed up immediately as the bitter …

From the Archives: Ape for Apples.

This Brittany visit report was originally written for the Newark CAMRA newsletter in July 2005. Mr & Mrs. Belvoir had a short visit to St. Barthlemy, a lovely quiet village in Brittany. Our hosts were Mike and Lynda Carrie, Newark branch CAMRA members, who moved out there about two years since and now try to earn a few Euros by …

From the Archives: Drowning Poole.

The second of my archive ramblings from Newark CAMRA’s newsletter is from July 2003. After several weeks of unseasonably warm weather, it was finally time for our planned long weekend trip south to Poole. No surprise, then that the weather broke the day I drove down to Wiltshire, raining torrentially for almost two days without stopping. Never mind, most of …

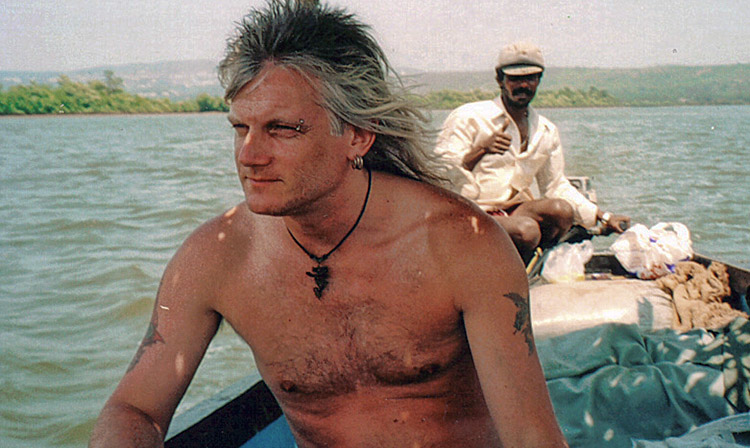

From the Archives: Go Go Goa.

For the next few posts, I thought I’d reproduce some beery ramblings I wrote for the local CAMRA newsletter. The following appeared in Newark CAMRA’s Beer Gutter Press and was from April 2001 India doesn’t immediately spring to mind when a real ale enthusiast thinks of heaven and they’d be right! In fact, its a beer desert, as BoldBelvoir discovered …